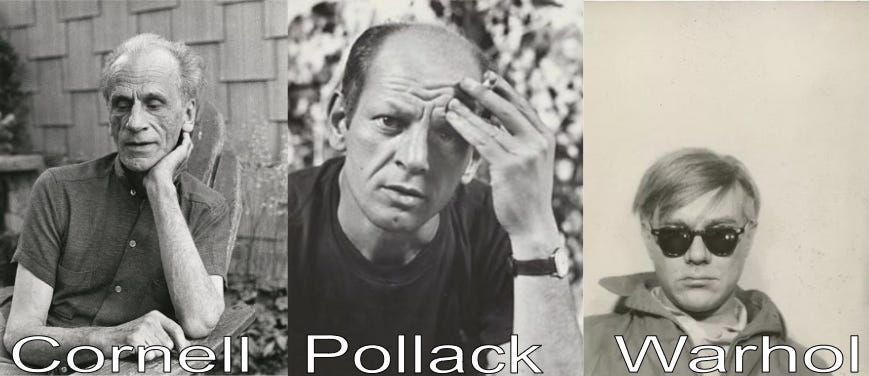

My master's thesis featured three artists; Andy Warhol, Jackson Pollock, and Joseph Cornell. I jokingly refer to them as the trifecta of men in art who had interesting relationships with their mothers. They also are a trifecta of men who were not particularly functional . Each had internal struggles and lived outside the realm of acceptable behavior. Maybe that’s why their biographies intrigued me.

Although I wrote The Spiritual Nature of Art in 2001, my interst in these subjects can be traced to a trip I took to New York City when I was in high school in 1975. On that spring break I joined groups of students from around the west touring the east coast. A highlight for me was visiting the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

(Looking back I now realize that I was among the small group of students from Colorado and and rest were largely from Utah where I live now. Strange coincidence…)

While I was at the museum, I was struck by the work of three artists that were very different. A large scale painting by Jackson Pollock which was overwhelming, the bold graphic pop art portraits by Andy Warhol, and a series of strange objects in wooden boxes made by Joseph Cornell.

Joseph Cornell's shadow boxes / Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2015

As a high school student, I was not familiar with Joseph Cornell, unlike Pollock or Warhol who were to me, superstars in the art world. This chance meeting with his work formed the beginning of a long interest in collage, ephemra, surrealism, and spirituality.

Cornell was born in 1903 in Nyack, New York to an upper class family. From 1929 until his death he lived with his mother and invalid brother in a modest house in a neighborhood called Utopia in Queens. Although he attended the prestigious Andover Preparatory Academy he never pursued a life typical of his peers. He didn’t marry, or climb a corporate ladder. Instead he diligently pursued his own path.

It was serendipitous events that led him to become a major figure in the art world. In the 1920’s he worked as a textile salesman to support his mother after his father died leaving the family with massive debts. He hated the job but managed to enjoy the freedom it allowed him to walk around the city. It was during that period Cornell discovered two passions that would change his life; Christian Science and Art.

Cornell was introduced to Christian Science by a co-worker. He visited the Christian Science reading rooms and studied the texts of its founder Mary Baker Eddy. Christian Scientists believe that the experience of the physical world is an illusion; including sickness. By cultivating one's spiritual nature the practitioner is awakened to the true reality. I would call this a “new thought” or “metaphysical” practice. Cornell may have been drawn to the intellectual idea that we can create our own experience of this life beyond what is perceived by others.

During the 1920’s he became aware of the Dada and Surrealist movement. He was familiar with the work of Marcel DuChamp, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Alberto Giacometti, Salvador Dalí, and by the metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chiric who exhibited in galleries he visited in Manhattan. Cornell began humbly, making simple collages out of paper at the kitchen table. Overtime these collages morphed into his contribution to the art world: the assemblage.

Assemblage is an artistic form or medium usually created on a defined substrate that consists of three-dimensional elements projecting out of or from the substrate. It is similar to collage, a two-dimensional medium.

A Parrot for Juan Gris, 1953-54.

In 1932 his work was included in the landmark exhibition “Surréalisme” at the Julien Levy Gallery. He had a solo exhibition at the same gallery later that year and his career took off from there. His work is included in major museums including the MOMA, the Tate in London and the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. His boxes have sold at Christies in excess of 5 million dollars. He died in 1972 at 69 years old.

Cornell was described as oddball in a review by Bruce Hailey (Art Forum). I would say he wasn’t an oddball. Instead he was radical independent in the art world. Although Cornell was an intellectual artist, his premise for making work was not an aesthetic game that artists like Duchamp were playing. His work was rooted in the spiritual. I think his belief system allowed him to create worlds within those boxes that spoke in a metaphysical language.

Years ago I attended a weekend workshop with Liz Kettle. The workshop shared a variety of techniques for transferring images onto fabric and creating mixed media collage. She’s a wonderful teacher. Since that time has developed “stitch meditation” that combines mindfulness with handwork. It was during this weekend that I made “Bookmark for Saint Teresa”.

The composition used one of a variety of visual structures suggested in the workshops’ handout. The cruciform is an arrangement where two lines intersect or cross. The term is used in architecture, botany, and religion. In art, the crossing of two lines creates stability in a composition. It is often used in abstraction. In my work, I used cross as both an artistic device and a reference to the subject matter.

Bookmark of Mother Teresa 24 x 30

At that time, I was like Cornell; able to wander around the art world in my own city of Denver during summer breaks from teaching. I discovered a spiritual community that was very distant from my Catholic upbringing where I learned to meditate and studied a variety of spiritual paths. This piece was both a learning experience in technique, but also an exploration of religious or spiritual imagery.

This exploration of the topic and a technique has been ongoing. In my next Substack I want to expand the backstory of the “Bookmark of Mother Teresa” with on going explorations of spirituality through art and connections that I have rediscovered after taking this off the wall to photograph.

Until Next Time

Margaret

I’m very familiar with Cornell’s work but didn’t know about his spiritual side. Thanks for enlightening me.